Masks, Masquerades and Cultural Evolution in the Time of Pandemic

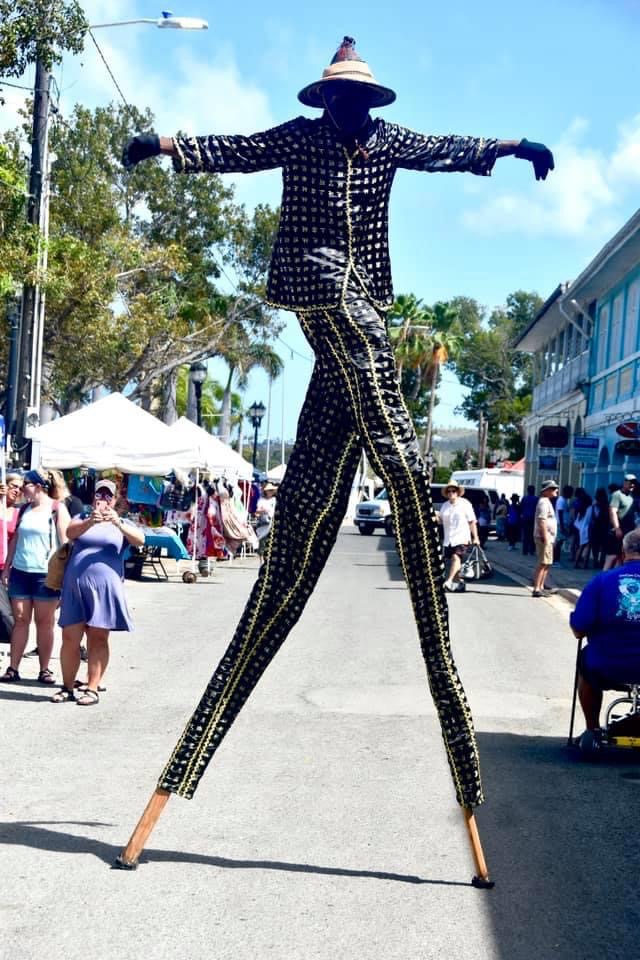

Traditional Moko Jumbies – Guardians of Culture. Photo courtesy Willard John.

by Monique Clendinen Watson

September 2020

Since late March, the familiar rhythms of our world have been disrupted by the global pandemic of 2020. The seasonal markers by which we acknowledge time and change have been smudged by fear of an unseen foe. In the Virgin Islands of the United States, we mark holidays and holy days with festivals and ceremonies that bring us together. We celebrate and display our artistry in music, visuals, crafts, dance, and foodways and in shared experiences that connect neighbors, visiting schoolmates, friends, and family of different generations in rituals of bonding and affirmation. Scattered across our calendars are the Crucian Christmas Festival, the Agricultural Fair, the Virgin Islands Carnival, Emancipation Day, the St. John Celebration, Bull and Bread Day and other events that are our collective expression of history, culture, and tradition. However, in this moment, for the health and survival of ourselves and our families, our masquerades and mass gatherings have been replaced with mask wearing and social distancing. When the sun set on the celebrations of 2019 and early 2020, no one could imagine that they may have been the last for the foreseeable future.

Pandemic restrictions have not dimmed the passion of Willard John or Chalana Brown for Virgin Islands art, history, and culture. Rather, they are using this universal time-out to discover more about themselves and their art. “Even though we are on pause, the mind and spirit never sleep,” said John, a Virgin Islands culture bearer in the Moko Jumbie tradition. “I have used this time to learn more about the history of the artform,” he said, writing and documenting what he knows for development into a curriculum with lesson plans. Brown, a multimedia artist, is turning to her art photography, taking self- portraits in modernized cultural wear at seldom visited St. Croix sugar mills and iconic town locations. Posted to social media, these portraits are aimed at reclaiming local spaces and redefining their meaning for herself and those who view them. “I go to each estate, spend time, take pictures and research stories about the people who once lived and worked there, she explained. “It is my way of joining the global movement of picturing black bodies in different places and asserting that ‘there is really no where that I cannot go.’”

John has been dancing, performing, and teaching the art of moko jumbie since the 1970s. “I did not choose this path, it chose me,” he explains. He was initially scared of dancing on stilts high above crowds and told his cousin, John Mcleverty as much when he was asked if he wanted to learn the craft. He was a recent graduate of Lincoln University who returned home to live and contribute to his community. While at college, he had met students from across the African diaspora and learned about their cultures and traditions. “I felt deprived because I did not know enough about my own history and culture,” he remembers. “When I came back, I wanted to immerse myself in something, so eventually I said yes.” Carnival of 1975 was the first time that John joined his cousin on the stilts. “I learned that my desire to learn had to be stronger than my fear.”

Brown’s first photo exhibit was the “Madras Headtie Art Series” which consisted of five digital portraits enhanced by computer graphics of five different women wearing madras headties. Initially, she did not see herself as an artist until as a TV reporter she did an interview with Virgin Islands artist LaVaughn Belle. “She opened my eyes to the fact that I did not have to be a trained painter to create art. I could use different media to express what I feel about the identities of Virgin Islands women.” Her passion for culture and its female expression was nurtured by her family, her mother Marjorie Brown and her great aunt Alice Petersen and others who lived their culture every day. “Growing up in a Virgin Islands household, wearing madras was a part of my culture.” She researched and found connections to the fabric in Asia, Europe, Africa and the Americas. While not an African fabric, the colors and patterns would have resonated with ancestors who no longer had access to kikoi or kente. “We found a way to hold on to our African identity even while being forced to wear certain fabrics,” she explained.

Becoming a moko jumbie was more than learning how to dance on stilts, said John. The moko jumbie tradition came to the Caribbean with enslaved West Africans. Practitioners tower over the people at festivals joining the spirits of the past, present and future together in ritual. He felt transformed once up on stilts. “I felt connected to my ancestors. A spiritualism comes over me and I become a part of the life of the people. I am nervous, apprehensive and encouraged.” While he does not judge those moko jumbies who dance shirtless and maskless, John says he upholds the tradition of covering and masking. His wife Corliss Solomon John, herself a dancer and tradition bearer creates and sews his outfits. They discuss materials and themes, making sure that they represent the spirit of the people. “Moko jumbies are up high and masked because they represent the powers of the Divine,” he explains. “That is why they cover themselves and do not show their human face. The lesson from the ancestors is that there is life, and there is life after death. We are sure about this life, but not absolutely sure about life after death. The mask represents what we do not know.” John agrees that it is an interesting turn of events that we are all now wearing masks as we navigate life and death issues. “If we want to curtail this pandemic, we all should wear masks for the good of all,” he said. “I wonder about those who feel it means they have to forego their “rights.”

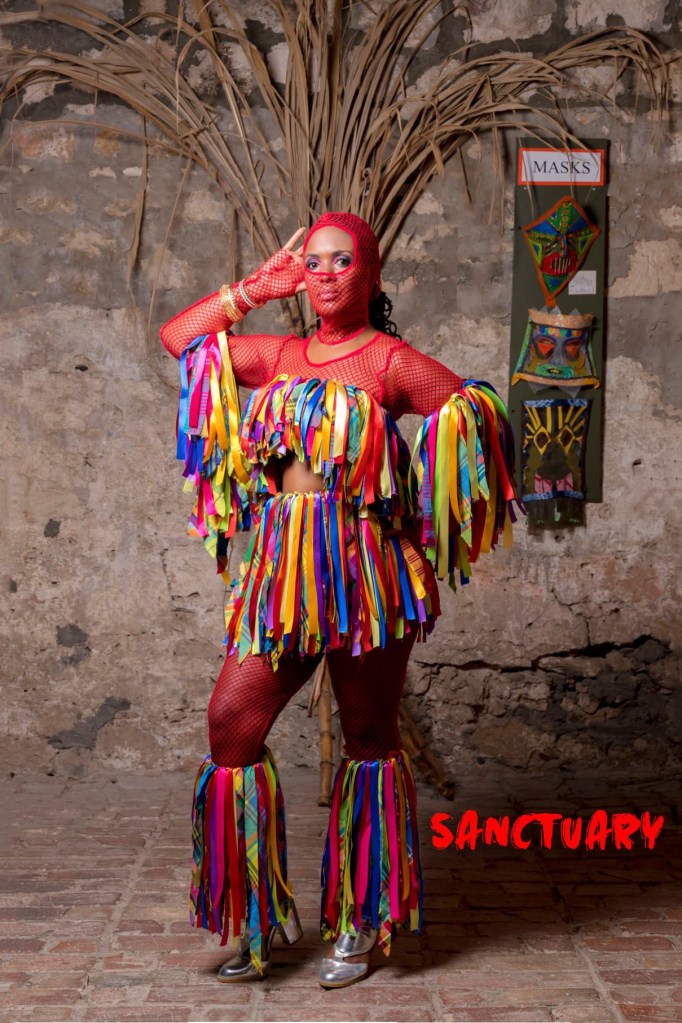

The red fishnet face coverings worn by members of the Sanctuary Troupe during the last Crucian Christmas Festival were an homage to the masquerading traditions in the Virgin Islands, the wider Caribbean and Africa, according to troupe founder Brown. “We held on to the traditions of those who did not want to reveal their identity and presented it in a more evolved, modern way,” she said. “We’re of African descent and we always see pictures of people in traditional dress with face coverings. While I don’t know all the reasons why, I know for sure it is in our DNA.” Brown and friends created Sanctuary to revisit traditional festival masquerade themes in a 21st century frame. Troupe members wore costumes made of madras and other traditionally worn fabric and broad brimmed hats. “Festival is rooted in the community’s desire to showcase politics, protest, sexuality and many other subjects,” she pointed out. She and others wanted to continue the dialogue around recent festival presentations. “Should we just mimic others, or should we explore and express our own identities?” she asked. Sanctuary masqueraders wanted to create “a safe haven for women to express their sexuality,” Brown said. “Our members wanted to celebrate and be comfortably clothed without being oversexualized.” While their numbers, 30 strong, were small by Adult Parade standards, Brown said they were able to share their music with masqueraders and individual entries like “John Bull,” on the route, expanding the scope of their presentation.

As an observer and student of the history, arts and culture of the U.S. Virgin Islands, it is clear to me that even before the pandemic, our islands were in the midst of a cultural renaissance. With the sustained representation of tradition bearers such as Stanley and the Ten Sleepless Knights, Richard Schrader and Cedelle Petersen and the combined new energy of LaVaughn Belle, Waldemar Brodhurst and Digby Stirdiron the seeds of our multicultural traditions are blossoming. With a strong African base and a seasoning of traditions from Europe, North and South America, and the Caribbean at-large, Virgin Islands culture is being reimagined. “Culture is not static,” emphasizes John. “It is dynamic and changes and reinvents itself. Whatever your craft, you have a responsibility to master it and know and understand its history,” he said. As our cultural narrative evolves, it is important that we retrieve through memory, experience current conditions and project into the future.

To learn more about Willard John, moko jumbies and his work to create curriculum around the artform, you can email him at jumbieproductions@msn.com or visit his Facebook page – Guardians of Culture Moko Jumbies. You can view Chalana Brown’s work, contact her and learn more about her quest to reclaim cultural spaces around St. Croix by visiting her Instagram page Chalana_vi or her blog at https://chalanabrownvi.blogspot.com. As the world we live in is global and interactive, I would like to hear from you who know and love St. Croix who may have stories, pictures or memories to share about Company Street or any other aspect about Virgin Islands history and culture. You can find this and other blogposts at www.companystreetchronicles.com or visit my Facebook page – @companystreetchronicles or on Twitter @companystreet59. You can email me at mcw@bluegaulinmedia.com.

Monique Clendinen Watson is a writer and public relations specialist who is from the U.S. Virgin Islands and who lives in Virginia. She owns a public relations firm, BlueGaulin Media Strategies, LLC. www.bluegaulinmedia.com. Photos used with permission of Shanna O’Reilly, Willard John and Chalana Brown. © Company Street Chronicles and Bluegaulinmedia are copyright protected. September 2020. All rights reserved. ©2020 BlueGaulin Media. All Rights Reserved.

2 Responses to “Masks, Masquerades and Cultural Evolution in the Time of Pandemic”

Wonderful and refreshing blog! Thanks for keeping us informed, Monique!! Much success to you.🙌🏼🙏🏽❤️

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Peaches! Want to do much more. Thanks for your support.

LikeLike